Miriam Sentler

Interview

Exploring the Underground Forest -

A Conversation with Miriam Sentler and Kristof Reulens (2022)

Dutch artist Miriam Sentler (1994, DE) is one of the residents at Jester in 2022. In conversation with Kristof Reulens, the coordinator for arts and heritage at the City of Genk, and Jester’s curator Alicja Melzacka, she is sharing her research and looking back at her three-week long stay at the Emile van Dorenmuseum.

Alicja Melzacka:

Miriam, as an artist and researcher, you’ve been dealing with fossil fuel landscapes for a while. How did your previous experience translate into the context of Genk? What astonished you?

Miriam Sentler:

When I came to Genk I had certain expectations regarding mining sites. For several years, I have been researching the lignite industry in North-Rhine Westphalia, where the local forest is disappearing, ecosystems are being excavated, birds and people are being driven out of the landscape. As it turned out, Genk is an entirely different context. I was confronted with the fact that there is so much nature around in the first place. It has to do with the different ways in which lignite and black coal are extracted – the first one requires excavation of large pieces of landscape, so-called ‘strip mining’, while the latter is found deep underground. So, I was coming from a barren landscape in Germany to a rich, ‘new’ landscape in Genk.

During my stay here, I soon discovered a very different kind of relationship with the landscape. I became interested in the fact that a lot of what’s now considered ‘nature’ has emerged because of the industry. In Genk, we are historically talking about a heath landscape, where there weren’t many trees to begin with – most of them were planted for industrial purposes. The so-called ‘mine arboretum’ is one example of such industrialisation of nature, but also the forest management by the wood industry, or the planting of trees to prevent the sand drifts, which was practised already in the mediaeval ages. In fact, humans have always shaped nature around here.

AM

In this new context, what triggered your interest the most? Have you found a new line of inquiry while working in Genk?

MS

I was most interested in the material agency of nature in relation to the industry – how, on the one hand, nature was exploited by the mining industry and, on the other hand, how plants and animals were assigned specific agency by the workers. It was something that occurred to me when I was looking into different linguistic expressions, for example: ‘de kanarie in de koolmijn’ (the canary in the coal mine) and ‘grenen spreekt voordat het breekt’ (pine speaks before it breaks). They convey an interesting sense of listening to that nature, and at the same time, industrialising and deploying it in a specific way, also in order to save lives. That’s what was perhaps the most striking to me, the agency that this exploitative industry itself assigned to nature. Then, the second part was, of course, the history of landscape painting in Genk, which I got to know during my stay at the Emile Van Dorenmuseum.

AM

You had an opportunity to live in the museum’s historical building, which was built by landscape painter Emile van Doren, one of the founders of the artists’ colony in Genk at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. What did you find the most interesting about this part of Genk’s history?

MS

One thing was certainly the idea of going back in time: the attitude of a painter going into the landscape and not drawing the emerging industry but looking away, towards the heath. It made me think of this sense of deep time one might experience in the middle of the ocean, where nothing really changes. I was fascinated in particular by the painting of a carbonised forest by Jan Habex, which is taking this notion of going back in time even further.

Kristof Reulens

I also find this painting fascinating. It was commissioned by the mine of Waterschei. Why did the coal mine industry find it necessary to commission a monumental painting showing the landscape before human interference? It might be seen as a kind of scientific illustration of the geological period from which the resource originated, but still, it is quite a paradoxical gesture.

MS

Another thing which I found fascinating about Genk, and which also relates to the history of a specific painting, was the healing power of this landscape. The birch trees in Genk were utilised in different ways: firstly, by the wood and coal industries, secondly, by the landscape painters, and thirdly, for medicinal purposes. Priest and physicist Sebastian Kneipp claimed that the birch forest would heal tuberculosis, and in Bokrijk, a sanatorium was built. This enormous agency of the trees is something I found really stimulating. This medicinal application of nature is portrayed in that painting of François Halkett from 1885, entitled Dans la sapinière. The painting explores the notion of disappearance – someone enters the forest, stays there for a while, and then disappears completely. Only the clothes are left behind.

KR

This painting is shrouded in mystery. We only know a story as put forward in an article in De Groene Amsterdamer, dated 1885, one year after the painting had been completed. The painting represents a woman suffering from tuberculosis, a lung disease strongly linked to the industrial revolution. She visited Genk because it was believed that the wind blowing across the heather grounds and in the pine forests was cleansing. This scene is depicted in the first panel, where you can see the sick woman accompanied by her sister. In the third panel, you can see the pine forest which is a little bit taller, indicating the passage of time. Amongst the trees, there is a black veil with flowers. The story in De Groene Amsterdammer tells us that the woman did not survive the treatment. It has not been confirmed, but my view is that it’s a personal history of the painter, François Halkett.

MS

In this story of trying to recuperate, to revive one’s body, I can see a kind of parallel with the state of the landscape itself. Compared to Germany’s disappearing forest, there is a ‘resurrecting’ forest in Genk, one that is still developing and still growing. This idea of resurrection is also represented by the so-called ‘canary resurrector’, which I came across during my research. It was a device used in the mining industry to revive birds which started to show signs of carbon monoxide poisoning.

These are different kinds of parallels, which I found in Genk, and which I want to work on further, primarily through sound. I think that sound is a suitable medium to map all this knowledge because sound specifically was utilised by the industry. Think of the crackling of wood, functioning as a warning against a mineshaft collapsing, and the singing of a canary, or rather its absence, when the carbon monoxide level would become dangerously high. This is precisely the idea of sentinel species, which can sense things humans cannot. I would like to look into this further with composer Drake Stoughton, to think about it in terms of sound and music history, where ‘resurrection’ is, of course, a common trope.

AM

Miriam, you worked with Drake before, on your sound piece ‘The Chase’, which you presented in Genk last year, during a lecture performance.

MS

‘The Chase’ emerged from my research into the lignite industry in Germany, and it was inspired by my family history. My great-grandfather was a miner coming from this area, and my grandfather always lamented the fact that his birthplace was excavated by the industry and turned into a lake. Starting from the lake, I researched the landscape and eventually ended up at Hambacher Forest, which is currently being excavated, amidst the protests of treetop activists.

In the mediaeval ages, Hambacher Forest used to be called ‘Burgewald’, which means the commons’ forest. There were certain rules of how to interact with this forest. The citizens were allowed to gather wood and berries, but they were not allowed to cut any trees or harm the forest. When the industrialists arrived there, about 200 years ago, they first started by rebranding the forest. Since then, it was no longer the commons’ forest but Hambacher Forest, related to the Hambacher mine. And so, the extraction could start. What remains of the forest today is only 10% of its original size.

‘The Chase’ was an attempt to archive the bird species of the disappearing forest because many people who were resettled from that area told us that what they missed the most were bird songs. We recorded the songs and transcribed them into a score. The resulting audio piece shows the impossibility of truly recording nature. With each line, you first hear the bird singing, followed by the musician trying to mimic the sound on the flute. But he can never actually ‘capture’ the bird, as if it was too smart for him.

AM

Could you tell us something more about the relationship between that project and your present research in Genk? You have been making on-site recordings, and you are going to work with Drake again – what approach do you assume this time?

MS

The new project is of course different, as it departs from a different context – while in Hambacher Forest things were disappearing, in Genk, they are emerging. That’s why, with Drake, we started talking about this resurrection in relation to music tropes. How were the religious chants written, where were they performed, and what was their social role? This is something still very apparent if you look at the effort put into constructing mine chapels, which in the end, also conveyed the power of the industry. Drake was also directly intrigued by the canary resurrector as a container for something, maybe even sound. We found it very particular that while the crackling of the pines served as a warning sign, in the case of the canary, it was the absence of sound that indicated the danger. To think about the resurrection is to think about death and life, about the absence of sound and the presence of sound.

KR

Now that I hear this story about the disappearance of the forest, I see some quite interesting parallels with Genk. The idea of a loss or a gain is different, and yet the same – I’ll try to explain why. You said that Hambacher Forest used to belong to the community. Also the heather grounds in Genk were called ‘gemene gronden’ (common lands). Everybody had the right to the land and could let their sheep graze on it. When in the 19th century, the government introduced the law of the savage lands, promoting the cultivation of pine forests – one of the few crops that could survive on the sandy soil – the locals protested and peasants went on strike because they were losing their communal grounds. It is a pretty similar development to the one you described in Hambacher Forest, with the industry taking over a common resource. So what you see now as a resurrection would not be perceived this way by the 19th-century farmers. They saw the coming of the pine forest as the death of their way of living. Who has the right to the landscape? How do these ideals change with time? There is always a communal idea behind, I think, being ‘the people’ vs ‘the industry, but it is always in movement. It’s a cycle, where you will always have the resurrection and the disappearance over and over again.

AM

Raymond Williams uses the metaphor of an elevator to illustrate this relativism of the notion of ‘nature’. He was referring specifically to the evolution of pastoral writing, but this metaphor might as well be adapted to other contexts. He said that no matter how far back we go in our analysis of the notion of nature (and its representations in literature, art, etc.), there has always been lamenting about the loss of a more ‘real’, more ‘natural’ way of living. He compares this to a moving elevator, which keeps going further backwards, constantly looking for a more utopian, arcadian vision of nature. This image of an elevator resonated strongly with me because it is rather unusual to spatialise the temporal dimension along the vertical axis. And this image of an elevator going underground, deep into geological time, resonates also with the context of the mine.

KR

A good example of this relativism is, for instance, the lake district of Genk – De Maten. Recently, many trees have been cut down there, which provoked a large protest. But that decision was actually taken by Natuurpunt, the keepers of this landscape, to preserve that landscape in its desired state. To protect this landscape, you have to keep it quite barren because the trees with their roots have an impact on the slope and the cascades and can disrupt the ecological system that developed in De Maten over the centuries. What makes it even more complex is the fact that there is nothing ‘natural’ about the system of lakes and cascades that this area is known for – it was man-made in the mediaeval ages to farm fish. But, of course, when the landscape painters arrived in Genk, they saw this large lake district and thought that it was ready to be painted. The reflection of light in the water was a big topic, especially in the 19th century. Historically, these aesthetic considerations also played a role in nature preservation. I know that when it was first spoken about founding a nature reserve in Genk, in the years before the First World War, there were several arguments put on the table – biodiversity was one, but the aesthetic view of the landscape was another one.

So again, we have clashing visions on what the ‘natural’ state is, and what is worth preserving. On top of that, we have different economic agendas, of how to use the land to one’s benefit, whether it’s for farming, wood or coal industry, agriculture, tourism… I’m pretty sure that Emile Van Doren or Armand Maclot would be behind the Natuurpunt when they were opening the landscape up again and cutting down the trees. But maybe from an ecological point of view, leaving the trees to grow and create a new biodiverse ecosystem might be an argument of today, so which argument do you choose?

MS

So, maybe there is no original landscape in Genk?

KR

Maybe that’s the landscape that Jan Habex painted? I don’t know.

KR

I want to still return to the idea of the sound underground and share an anecdote about it. When the coal mines started to be active in this region, after the First World War, wood was no longer used to reinforce the mineshafts, it was substituted by steel support. I think that the mine arboretum, which was cultivated as a kind of testing ground for material research, quickly became obsolete. Of course, wood was still used for other than structural purposes in the mines. I also think that wood would have lost its signalling function because, in the 20th century, conveyor belts were introduced underground, and there was this constant noise which was absent from the 19th-century mines. The same goes for the canaries, which eventually were substituted by special mine lamps.

However, what I always found interesting were the stories about another kind of sound, told by the miners from this region. They said that in the mineshafts, you could hear the loud chirping of the crickets, which were transported there with the wood. This was the only natural sound they could hear…

MS

That’s fascinating. It is as if different times and stages of the industry had different natural sounds accompanying them. I think that there is a potential in bringing these various temporalities and sounds together in a hybrid soundscape: the geological time, the historical time, the idealised time; the trees, the birds, and the crickets. It’s quite evocative to imagine how they populate this forest, deep underground…

This project has been realised in collaboration with Emile van Doren museum,with the kind support of the city of Genk, the Flemish Community, O&O Subsidy/ CBK Rotterdam, and the members of Jester(formerly CIAP & FLACC)

Sound recording in De Maten, a natural reserve in Genk, an old mining town in Belgium. Photo: Johan Schoonaerts, © Miriam Sentler

Sound recording in De Maten, a natural reserve in Genk, an old mining town in Belgium. Photo: Johan Schoonaerts, © Miriam SentlerConstruction of Waterschei Genk mine with pine trees, from the archive of Waterschei, date unknown.

Construction of Waterschei Genk mine with pine trees, from the archive of Waterschei, date unknown.

Steenkolenoerwoud in de oertijd, Jan Habex. 1945, collection of Emile van Dorenmuseum.

François Halkett, In het Dennenbos –Dans la Sapinière,1884, sketch in the collection of the Emile van Dorenmuseum.

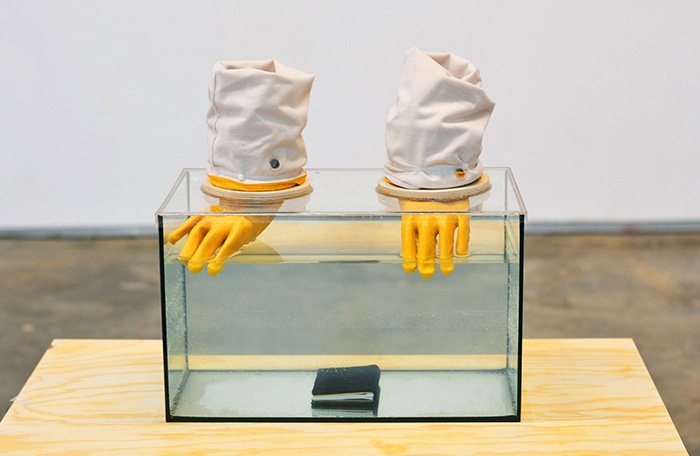

Canary reviver, Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Canary reviver, Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

The Chase, Drake Stoughton’s and Miriam Sentler’s first collaboration in 2020/2021. © Miriam Sentler

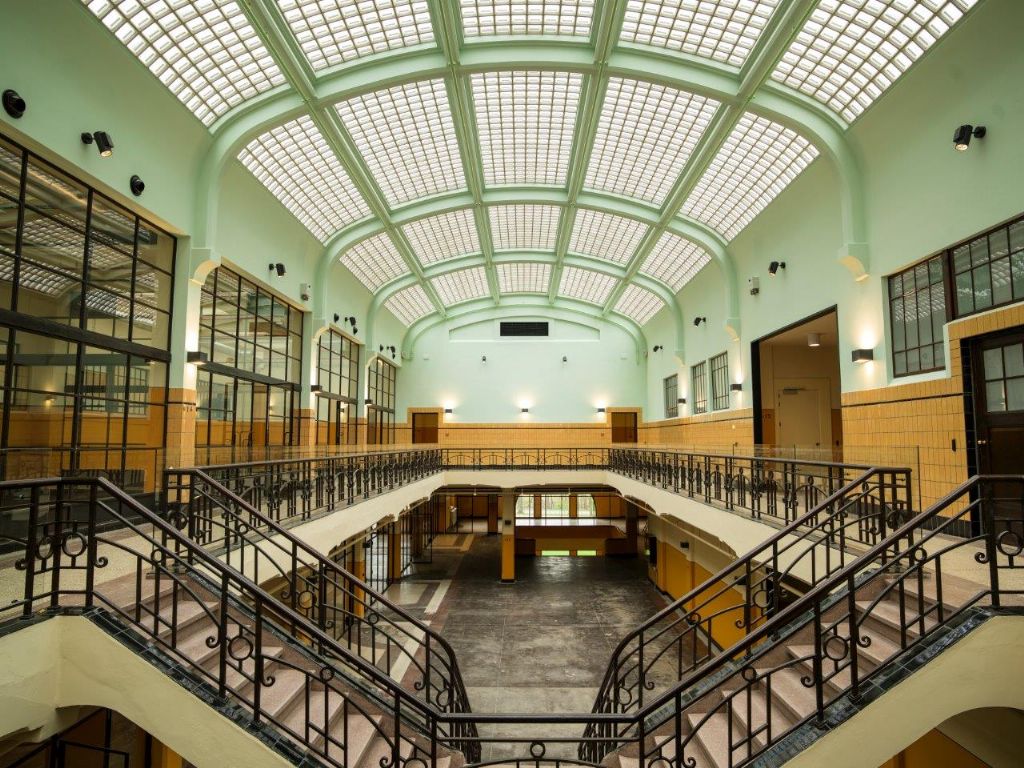

The Chase, Drake Stoughton’s and Miriam Sentler’s first collaboration in 2020/2021. © Miriam Sentler Thor Central, Waterschei Mine Genk (BE). © Stad Genk

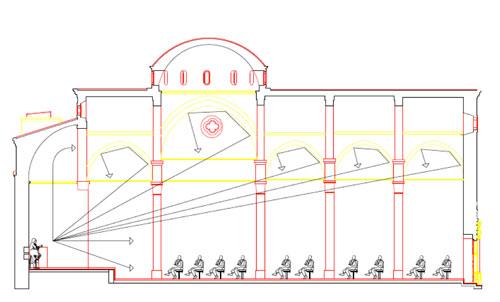

Thor Central, Waterschei Mine Genk (BE). © Stad Genk Section of church that shows basic components in system of acoustical performance in main prayer hall. © Filiz Kocyigit

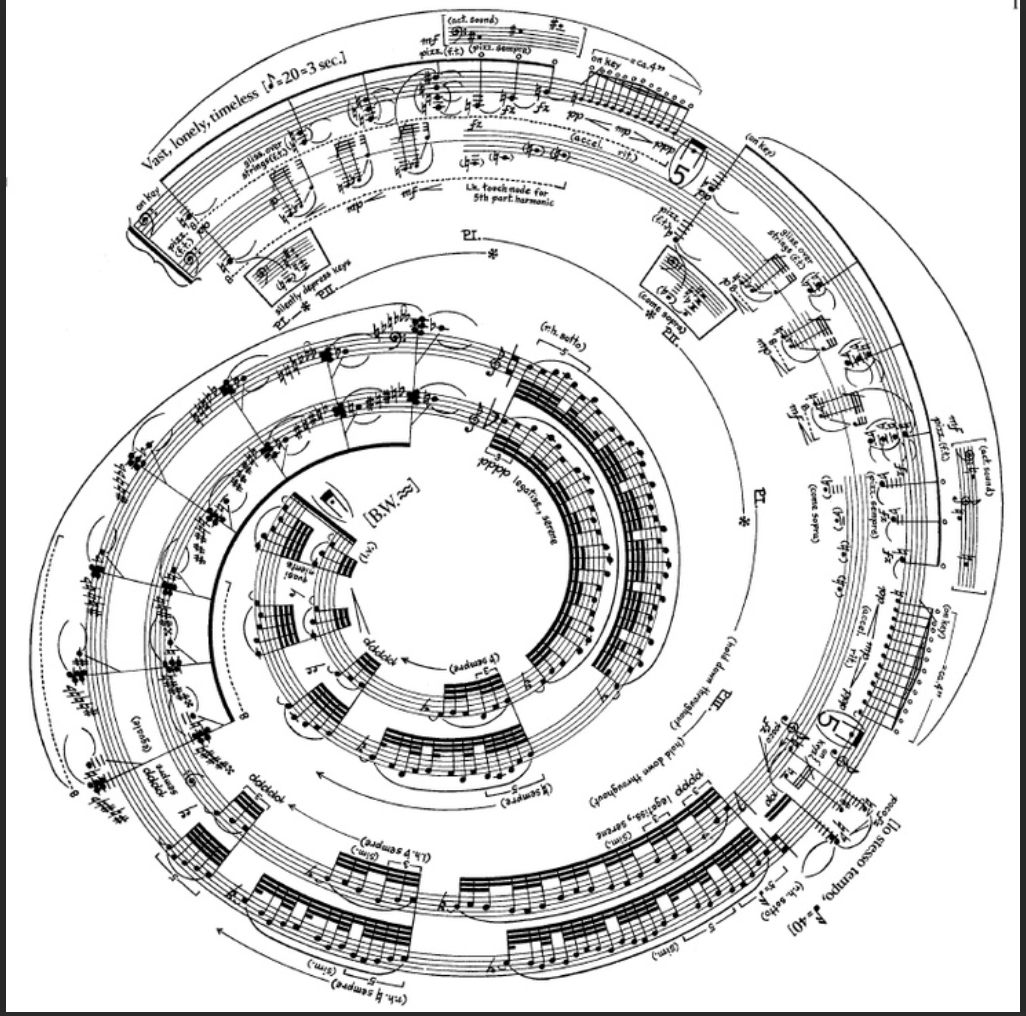

Section of church that shows basic components in system of acoustical performance in main prayer hall. © Filiz Kocyigit Spiral cord composition by George Crumb (b. 1929)

Spiral cord composition by George Crumb (b. 1929) Emile Van Doren (1865-1949) - Bloei van de gagel, landscape paining of De Maten district in Genk.

Emile Van Doren (1865-1949) - Bloei van de gagel, landscape paining of De Maten district in Genk.